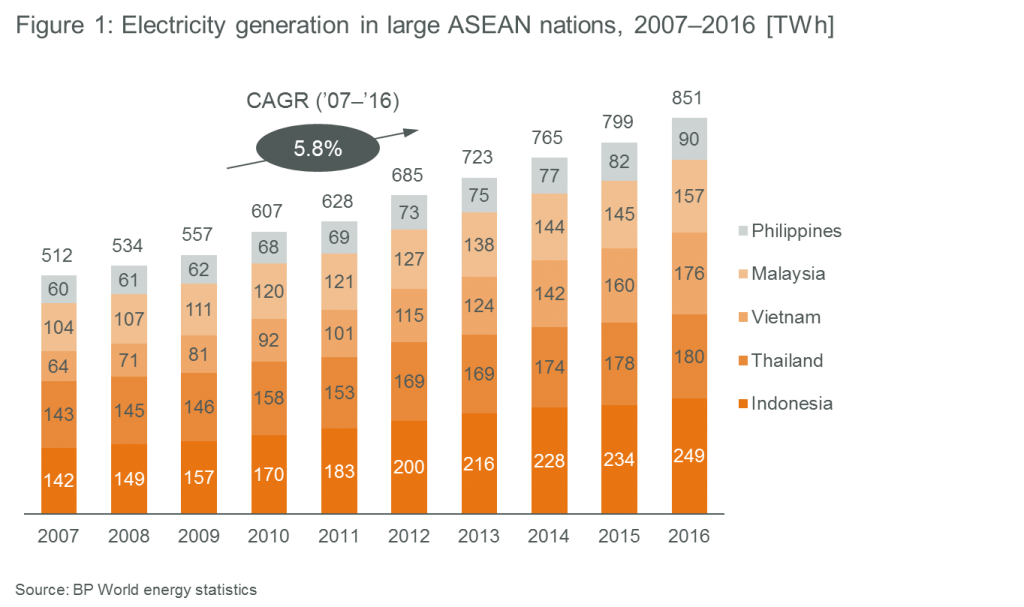

The need to install additional power generation continues to be one of the most relevant issues in Southeast Asia. It’s a region with GDP growth rates of above 6% p.a. during the past decade[1] and where around one-fifth of its population (~25% larger than that of the EU) is still without access to electricity.

Besides striving to meet the power demand, the growing dependence on fossil-based power generation and the increasing costs in providing power to its consumers have been the main challenges faced by utilities in the past decade. Unsubsidized electricity prices range between USD 0.13[2] to USD 0.30[3] in the region today. If we exclude the ultra-developed and wealthy city-state of Singapore, the GDP per capita only ranges between 4%–27% of the EU average, and therefore exposes the majority of Southeast Asian consumers to even higher burdens compared to consumers elsewhere, for example, in the EU.

In recent years many plans for additional conventional power plants have encountered fierce opposition from locals. Even in more authoritarian governed countries in Southeast Asia, this has led to a substantial cancellation of such power plant projects. For example, in Thailand, a long-pursued plan for a 3,200 MW coal-fired power plant in the province of Prachuap Khiri Khan had to be cancelled due to public opposition. Of the two coal power plants currently under development, the 800 MW plant planned for Krabi also faced strong criticism from the local population including a hunger strike and led to the Thai government rejecting the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in 2015. In February this year, the Thai energy ministry declared it will study the plans for the Krabi coal power plant for an additional three years. The only existing coal fired power plant of the government, which is targeting 8,800 MW of coal power in Thailand, is the 2,400 MW plant in Lampang.

The power generation and distribution structures currently operative in Southeast Asia are either under the control of state-owned monopoly utility companies, which is the case in Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia and Laos. Other countries, such as the Philippines, Malaysia and Myanmar, have already liberalized or somewhat liberalized their utility markets. Even in those markets where the distribution of electricity is under state-owned monopoly, the power generation assets, if not already owned and operated by the utilities themselves, are often owned and operated by Independent Power Producers (IPPs), which is the case in Thailand making up about 25% of power generation capacity. The history of allowing private players to invest into and operate such power generation capacities (obviously stemming from the lack of investment capabilities by those governments and their state-run utilities) has resulted in the development of many experienced local, national and regional IPP companies. Some of them are quite large.

Renewables on the rise in Southeast Asia, albeit at different speeds

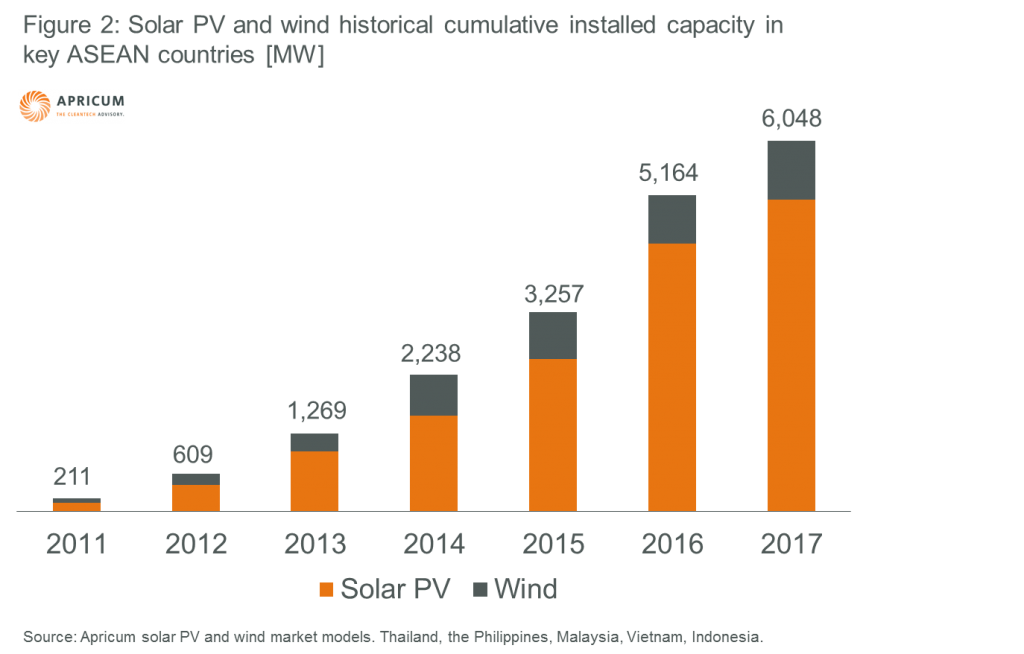

At the beginning of this current decade, the implementation of renewable energies in the region began on a utility scale with Thailand taking the lead after the introduction of the FiT Adder-Scheme for solar power plants of up to 90 MW in size. Other feed-in-tariff programmes for renewable energies, such as solar, wind and biomass, followed – not only in Thailand, but also in Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam and recently in Indonesia.

Most recently PV solar in particular has become an alternative to ever increasing prices from the utilities for the consumers in many of the Southeast Asian countries.

Commercial & industrial (C&I) roof-top solar is especially experiencing rapid implementation where it is unhindered by red tape or regulatory constraints. It is already economically feasible without any subsidies in most cases, allows for substantial cost savings, benefits power supply security in many areas with common power outages and also allows the companies to improve their corporate CO2 footprint.

Despite some costly and bureaucratic regulatory barriers, which appear to serve no sensible purpose, there are now many drivers of the expected exponential growth in the implementation of renewable energy capacities. The commitments made under COP21 require the ASEAN nations to accelerate their adaption of renewable energies. This has recently resulted in the revision of initial capacity targets and also in the legislation to achieve those targets. Further liberalization of the utility sector in ASEAN is also progressing. Thailand has now announced the publication of a new Power Development Plan (PDP) in March this year, which is expected to entail not only increased renewable energy targets but also elements of liberalization of the distribution of renewable energies outside the monopoly of EGAT and PEA.

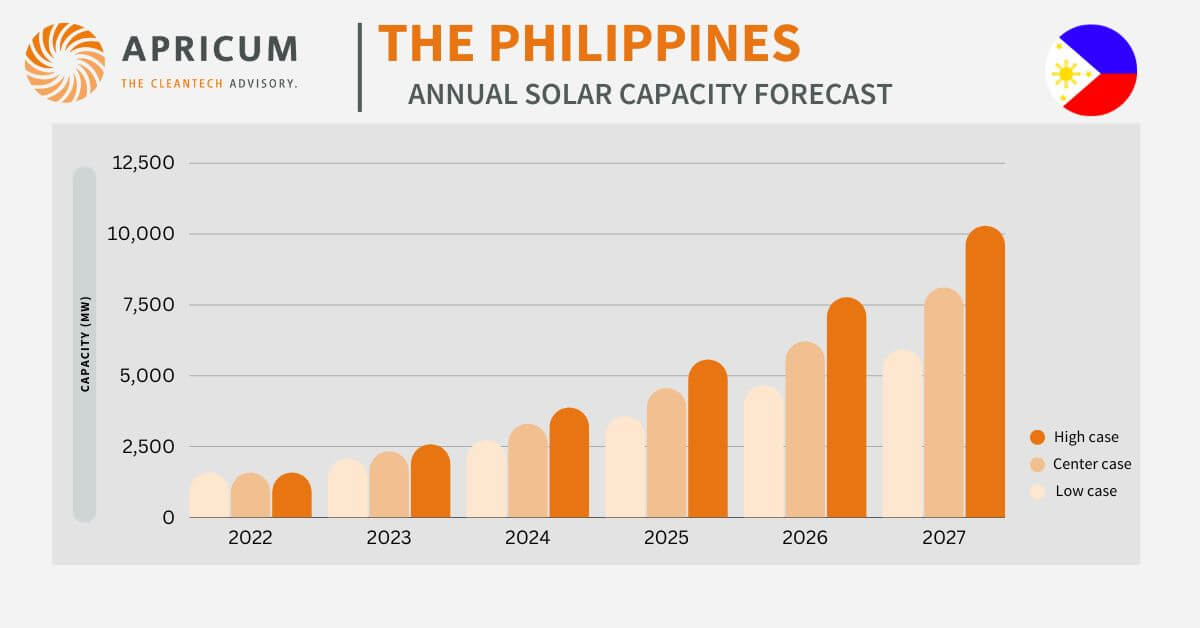

In the Philippines, the long awaited Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) legislation was signed by the Secretary of the Department of Energy (DOE) in December 2017 and will obligate any power generation or power distribution company to source an agreed portion of their energy supply from eligible renewable energy sources. Effective from 2020 onwards, the RPS requires a minimum annual incremental renewable energy percentage to be sold by mandated participants. It is initially set at a minimum of 1% and applied to net electricity sales or annual energy demand for the next 10 years. Furthermore, so called “contestable customers” (larger C&I consumers) have recently been given liberty to choose their power supply outside their local public distribution utility cooperative (DU), which also gives greater market access to renewable energy IPPs to cater for potential industrial off-takers with low cost RE power.

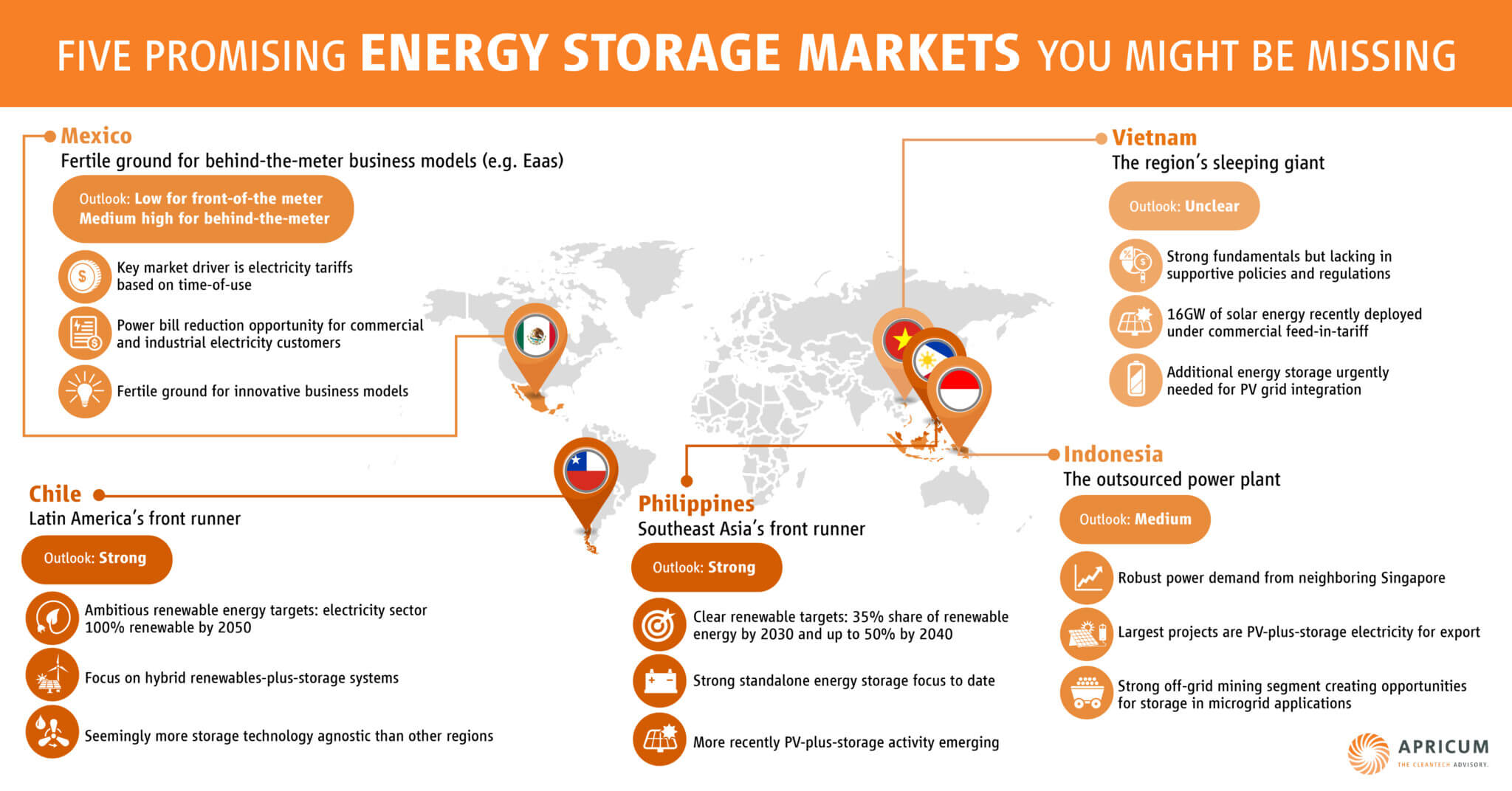

Some other markets in the region, such as Vietnam and Indonesia, clearly have to catch up on the development of RE. Vietnam, after some bumpy years in regulation and FiT determination for wind power, has now established about 200 MW of wind power and is expected to have about 500 to 850 MW in solar power installed through the upcoming FIT by 2019. Indonesia is significantly lagging behind its power development targets for renewable energy. So far, the largest country in the region with its population of 250 million, has achieved almost nothing in terms of renewable energy development. Its solar power target of 5 GW by 2020 seems like an illusion considering that so far only about 80 MW are in operation and 45 MW have been given commitments for PPAs with PLN in April 2017, which have not been constructed since. The FiT tender for 250 MW of solar that was expected to pilot the solar surge in the country last year has also not advanced. The tender requirements are viewed by many developers to be unfeasible and it remains uncertain what will materialize from this initiative.

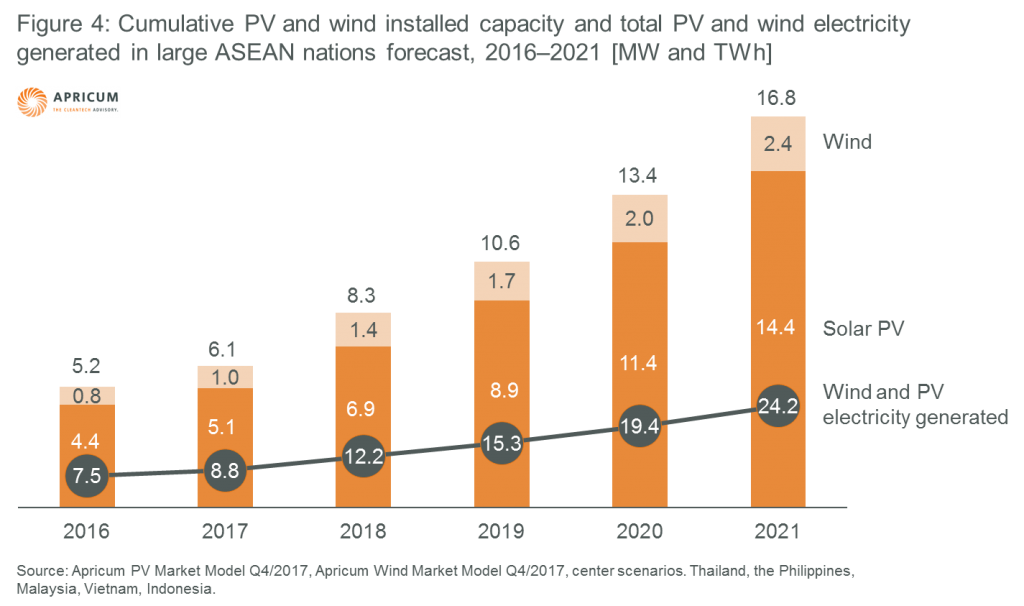

In summary, the expected growth for RE in Southeast Asia will be driven by the C&I segment with bilateral B2B solutions, an expanded market penetration of RE by IPPs and utilities due to their economics and potential to grow their businesses, and by the additional government policies and programmes to enhance RE energy capacity to meet their COP21 targets.

RE will soon shake up the power sector in Southeast Asia. Lessons can be learned from Europe

In Europe, about a decade ago renewable energy began its process of disrupting the power industry structures that were considered ironclad by its oligopoly tycoons. Let’s look at the example of Germany here: The country was basically divided by the four large utility companies into individual territories. The “Big 4” (RWE, EnBW, Vattenfall, E.ON) once controlled more than 90% of Germany’s electricity generation and distribution. This all changed with the political decision of the Social Democrats and the Green Party in 1998 to transform the energy system from fossil and nuclear based generation into renewables. As part of this energy transition, the first feed-in-tariff system for renewable energies world-wide in 2000 was introduced. By 2008, Germany had become the biggest market for renewable energies by far and had managed to develop a renewable energy industry that had scaled-up its manufacturing capabilities of solar and wind components to a level of mass production. At this point, the future and relevance of renewable energies in the German energy infrastructure was clear and irreversible.

With the introduction of the Renewable Energy Law (EEG) in 2000, it is fair to say those four large utilities considered renewable energies to be too small (RE made up less than 6% of the total power generation mix), too unimportant and without any meaningful potential to ever play a role and neglected any substantial involvement in the topic. A few years later when the utilities had to witness the constant rise of renewable energy (in 2008 RE already made up more than 15% of the power mix) and the resulting effect that they were obligated to connect all those RE power plants to their grids, they started to regard RE as a threat and unleashed their lobbying power against them. Only later when they had to acknowledge that there is no future without RE did they start to embrace them – unfortunately, it was too late. In 2017 renewable energy accounted for 36% of the power mix in Germany. Although the Big 4 held more than 85% of the country’s power market in 2008, today it has now declined to less than 60%.

In the same period, smaller regional utilities jumped on the RE bandwagon early on and grew in generation capacity, profitability and introduced sustainable business models. Some, such as the Stadtwerke München, which is owned by the city of Munich, started aggressively adopting renewable energies in 2008. By the end of last year, Stadtwerke München had 42% of RE in its electricity mix, whereas RWE (now Innogy SE) could only manage 3%. Stadtwerke München was able to increase its revenue by 40% since 2012, whereas RWE saw its revenue decline by 14% in the same period. Stadtwerke München is expected to meet all of Munich’s power demand through renewable energies alone by 2025.

Was the decline of the larger utilities inevitable? Clearly not considering the rise of Stadtwerke München and others by adopting business models for renewable energies early on. For their Southeast Asian peers, now may be the chance to accumulate even more growth with smart business models in renewable energies.

Southeast Asia could well experience a change to its power sector of seismic proportions

We may very well see a greater acceleration in the disruptive force of renewables in Southeast Asia than we did in Europe due to two reasons: 1) Southeast Asia has an urgent need for additional power generation capacity (whereas Germany, for example, is transitioning into renewables from an existing sufficient and fully functioning power infrastructure) 2) today’s very competitive costs of renewable energies.

New business models for power supply are already in the pilot stage

The constant need to expand the power and grid infrastructure in Southeast Asia is likely to result in substantial new renewable energy generation capacity – mostly low to medium voltage utility solar applications, which have become increasingly cost-effective in recent years.

In this environment of strong demand for additional power generation capacity, weak grid infrastructures and some maturity in low-cost renewable energy production; there are several business models on the rise in Southeast Asia that pose risks – and also opportunities – for utility companies.

With the steep decline of PV solar costs, C&I solar applications have become a real alternative for large power consumers in almost all of Southeast Asia. Even in Thailand where electricity costs are moderate, average cost savings of more than 15% of the price from the grid per kWh of solar power are possible to achieve. In markets with even higher prices from the grid, such as the Philippines, the economics for the installation of C&I solar power plants – mostly large roof-tops – are even more attractive. In most of the ASEAN countries, utility electricity tariffs have peak rates for customers that are highest during daytime; this provides an even better business case for such solar power solutions. A regional solar PV developer and solar IPP just announced additional projects for C&I clients in this segment in Thailand at the beginning of this year. The Philippine retail giant SM rolled out its very own solar roof-top initiative in 2017.

Apricum estimates that one-third of renewable energy power generation in Southeast Asia will come from the C&I segment by 2023. This will account for a substantial portion of current power consumption from utilities. It also poses a market share risk for utilities that are not willing to offer their customers solar power solutions.

Even greater – at least in terms of future market share distribution – are the risks for utilities regarding the customers they are currently not serving (the tens of millions that do not have access to power yet). Consider the thousands of islands throughout this region with limited or no electrical infrastructure. They present some of the most attractive short-term opportunities for renewable energy and storage. In many of these areas the industry is likely to adopt a more distributed approach to grid development, using more local power generation and microgrid systems.

IFC expects Southeast Asia to account for a substantial portion of the future deployment of energy storage systems (ESS), often in combination with decentralized renewable energy power generation.

The competitiveness of solar in combination with storage is clearly already there, where the region is affected by limited and unreliable power infrastructure. Many regions and islands in the south of the Philippines for example, lack any provision of power from a public utility. If connected to the grid at all, the power generation infrastructure operated by a local distribution utility is most likely based on diesel generators. The LCOE of a smaller utility solar + storage system is in the range of USD 0.14 per kWh. Compared to the alternative current LCOE of a local utility’s diesel-powered system, the solar + storage application has an amortization period of only 7 years and produces an IRR of mid-teen numbers – without any leverage from debt project financing, which is clearly not available at this point in time for such projects.

Therefore, next to the classic grid connected utility-scale renewable energy power generation, PV solar + storage for additional power generation infrastructure at the utility level or in C&I applications are clearly business models that will be adapted and present opportunities for the stakeholders in the Southeast Asian power sector.

The risks for conventional utilities of missing out on the development of RE in Southeast Asia

The question now remains: Who will be successful in claiming their stake in the future of power generation? The utility sector in Southeast Asia has the advantage of learning from the failures of their large European peers. They have the benefit of engaging in renewable energies at a point where they are economically viable and cost competitive – but they also have the obligation to set foot into the future of a distributed clean energy infrastructure if they expect to maintain their current relevance.

The competition will come not only from potential foreign utility companies that are already active in the renewable sector globally, but also from the numerous local and regional IPPs that are eager to adapt the new business models of distributed renewable energy generation and use further liberalization of the power sector to their advantages.

In any case: It will be disruptive – there will be winners and sore losers. The consumers will benefit from the rise of renewable energies by getting access to electricity where it was not available before, by being less exposed to environmental risks from fossil power plants and, of course, by saving money.

Apricum offers a range of services to support companies in successfully expanding into new markets and technologies. In particular, it has advised a number of the biggest utilities in Europe in entering the renewable energy sector. For more information on how Apricum can support you in developing your business in Southeast Asia’s renewable energy markets, please contact Nikolai Dobrott.

[1] CAGR from 2008 to 2018e, source Statista

[2] average on-peak/off-peak rate PEA Thailand from 6am to 9pm in 2017 of THB 4.336/kWh

[3] PHP 15.2/kWh in south Mindanao, Philippines