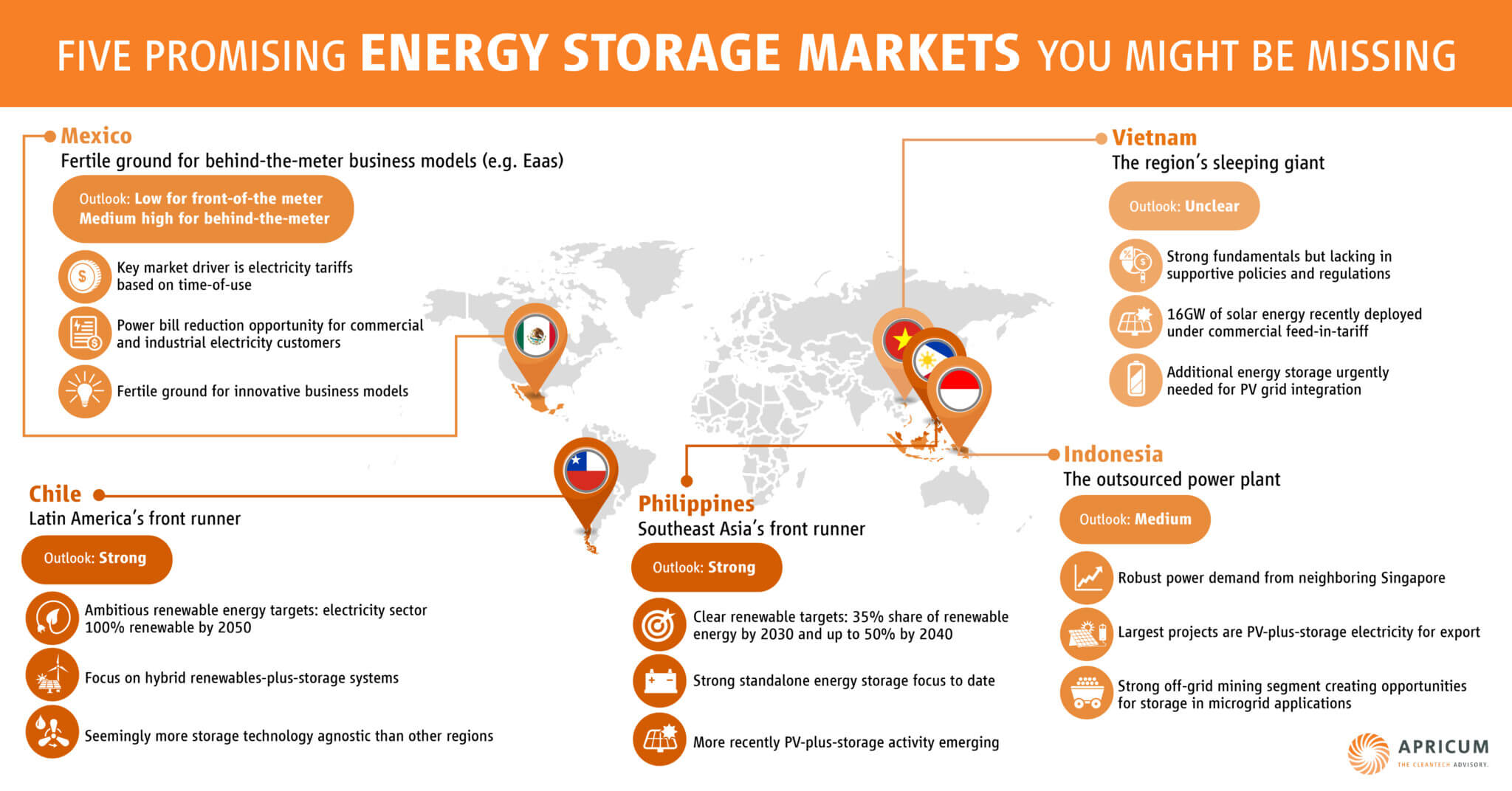

Through our day-to-day work around the globe, Apricum has gained deep insights about the dynamics of the energy storage markets and what it takes to be successful not only today, but also in a few years from now. Driven by the specific market characteristics, we identified certain “ingredients” of which an energy storage company’s business model should comprise to be one of the winning teams.

Let’s have a look at the five ingredients we at Apricum found most important:

Ingredient No 1: Remain flexible – be able to adjust swiftly to changing market conditions

One of the key advantages of energy storage is the vast amount of use cases it can serve. This is in contrast to, for example, solar, which is targeting basically one major use case – squeezing as much energy as possible out of the sun. But the high number of addressable use cases makes energy storage an extremely complex animal, as for each use case

- there is varying demand, depending on the individual challenges in each energy market,

- storage is competing with other alternatives mainly on a cost basis, and costs develop differently for a vast array of storage technologies available, and

- dynamic regulatory frameworks add additional complexity

Therefore, it’s hard to predict which use case will be attractive in which market – and for how long. In fact, we see “pockets of opportunities” opening up – but also closing – rapidly. Take the Primary Control Reserve – or PCR – market in Germany for example, where stagnating demand meets an ever increasing number of utility-scale storage installations and also aggregated distributed storage units compete with traditional suppliers. This specific pocket of opportunity is closing, so better make sure your business is not closing along with it.

A flexible business model is a must. It has to be constantly reviewed and updated depending on what’s going on in the market.

To ensure this flexibility, do not lock in on a specific technology but keep a tech-agnostic approach. If you are a technology company, maintain a high “flexibility by design” at your interfaces to other components, for example, inverters.

Also, do not lock in on a specific use case or, in other words, a specific mode of operation of the storage unit. Accommodate remote software updates or allow easy modifications of your hardware.

Enter into flexible partnerships, make sure you have contracts that are easy to cancel or at least offer enough degrees of freedom, e.g., warranties that enable the mode of operation of the storage system to be changed.

Last but not least, you need to maintain an excellent market understanding, in order to know what needs to be adapted and when.

Ingredient No 2: Continue to reduce costs – there will always be multiple alternatives competing

For the storage installations we see today, cost competitiveness did not always play a major role: A lot of the utility-scale units are pilot plants to test what can be done with storage. And in the residential market, sales are rather driven by early adopters than return-maximizers.

In this current market stage, there is enough room for a plenitude of players even with very small volumes – for example, the German residential storage market has about 48 different suppliers at the moment.

But this is going to change. On the way to a mass market for energy storage, more cost-sensitive customers will have to be convinced by lower prices, leading to more fierce competition and consolidation.

And in most markets you not only have to compete against other energy storage players, but also against non-storage solutions. For each use case, you have “incumbent” and therefore well-tested alternatives to storage (e.g., gas peakers, grid extension…) that can be hard to beat.

So how does one become more cost competitive? When people talk about “decreasing costs of energy storage”, in most cases they mean capex. The most important way to get this down is to quickly boost volumes to take advantage of economies of scale. In parallel, in particular if you are a start-up in energy storage, you need to improve your product design, which could include using materials that are less costly or that increase the overall performance.

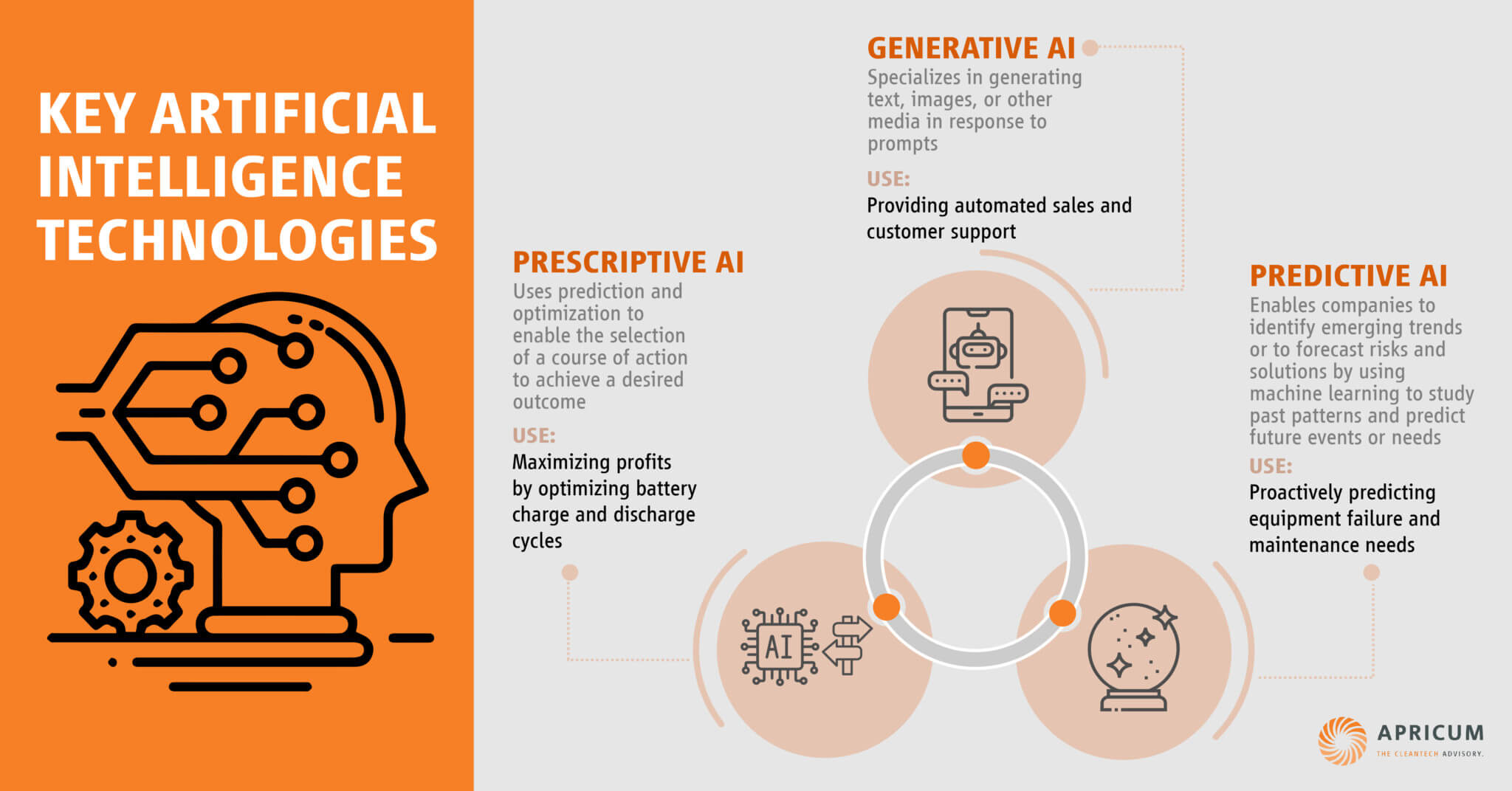

But capex is only one “influencer” of the lifetime costs of energy storage (e.g., LCOS), there is more you can do. For example, by combining use cases, you can increase the number of cycles and thereby the utilization of your energy storage unit. Hence, if the primary use case, the technology’s calendar lifetime and regulatory frameworks allow for it, benefit stacking is a good way to reduce LCOS. Another cost influencer is lifetime, which can be improved by optimizing how the battery is run. For example, studies by French TSO RTE show that by optimizing the operation of the battery the lifetime impact can be reduced by 36% with a minimal deviation from the optimal service delivery.

Plus, you should start thinking “outside the (storage) box”: There is more than just hardware. For example, the installation of a residential storage system in Germany can cost up to EUR 1,500. Finding ways to decrease installation times, therefore, can be a major cost advantage – outside of capex reductions.

Ingredient No 3: Tap into new revenue streams – and go where the value is

Next to reducing costs, you should think about ways to expand your accessible market potential and revenue streams to drive up profits.

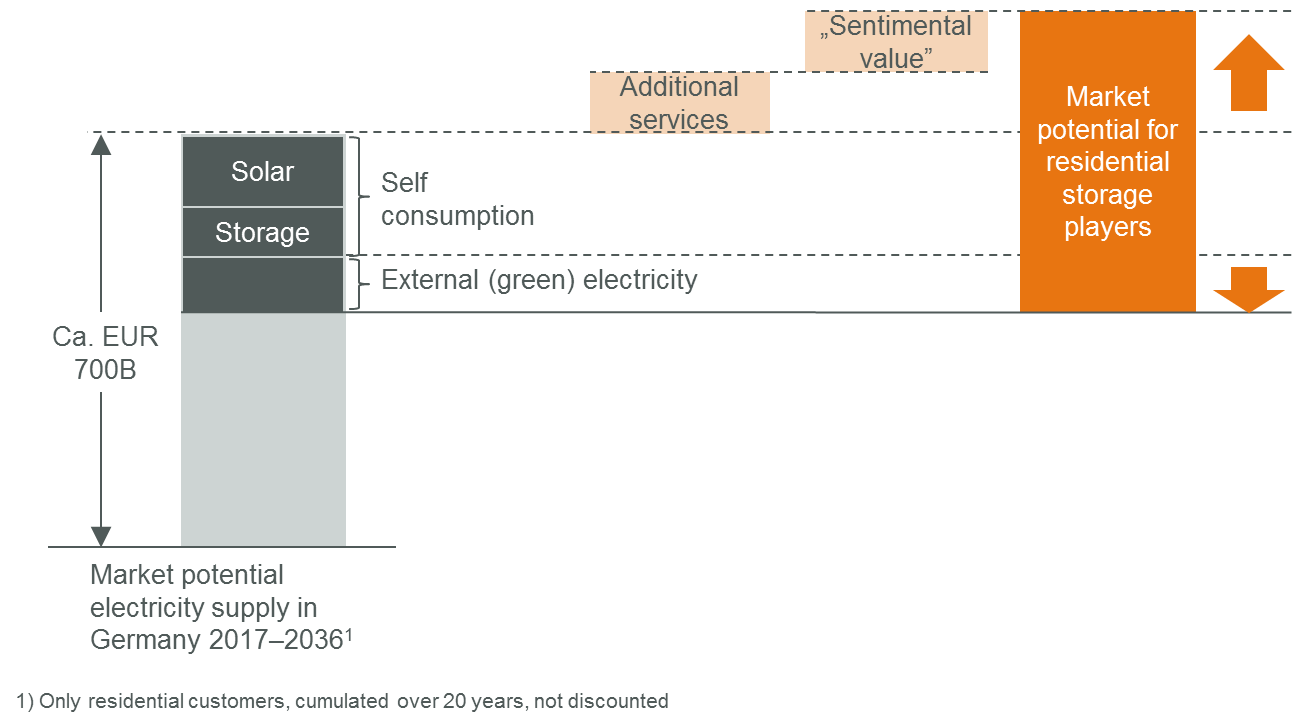

For example, a residential storage supplier with a “classic” business model sells energy storage units to its customers and thereby helps them to reduce the amount of energy purchased from the grid through increased self-consumption of rooftop PV power. The customer’s money available for purchasing energy is redirected from the utility to the storage company, which thereby captures a certain share of the “conventional” market potential for electricity supply.

If the company starts offering a full-service package and provides the residual amount of (green) electricity needed, this share can be further increased.

As illustrated in Figure 1 below, the residential player can now start aggregating its deployed devices and tapping into market potential beyond the conventional one, by offering ancillary services to the grid for example. Plus, certain premiums can be added for rather “sentimental values” such as autarky.

Figure 1: Example expansion of market potential for residential storage

At the end of the day, all of these values add up and result in a much juicier market potential than the “classic” business model would have provided. As a prerequisite, you need of course to understand where the most value is allocated along your value chain – and adapt your business model accordingly. In our residential storage example, this means expanding downstream and becoming a service provider in addition to offering the hardware alone. This will allow you to also capture value from neighboring value chains and realize increased revenue streams as described before.

Ingredient No 4: Be proactive – don’t wait for opportunities to come to you

No one has really waited for energy storage; there have always been incumbent solutions that could do the job as well. Hence, do not rely on clients beating a path to your door to get it.

Instead, you might have to explain to your customers what benefits storage can provide for them. But first of all, you have to find these customers, or better still, find the problems you can solve with your storage offering, for example, reducing grid fees, which differ a lot across Germany.

If a commercial or industrial company manages to keep its peak load out of a certain peak window defined by the German DSO, it can save up to 80% on grid fees – hence, this storage use case is very attractive for customer segments paying expensive grid fees and who have a suitable load profile. Often, however, these customers are not even aware of this saving opportunity, so you need to find them and enlighten them. When reaching out to them, make sure you have a crisp way of explaining your value proposition. Behind the curtain, there can be extremely complex financial and technological architecture in place to make the claim happen, but what the client sees must be uncomplicated and easy to grasp.

If executed correctly, proactiveness helps you to tap into new revenue streams that are less obvious and that are facing less competition in contrast to public tenders. And don’t limit yourself to your home market only – there are many problems to solve for other countries’ customers as well.

Ingredient No 5: Be bankable – ensure secure, sustainable cash flows

The holy, and to date somewhat elusive, grail of energy storage remains project financing. While there are various types of risk in an energy storage project that need to be mitigated, such as technology or construction risk, we see the market risk as the most critical for achieving bankability for project financing – and at the same time, the most difficult one to mitigate.

Looking at PV and wind markets in the past, a key reason for the huge success of feed-in-tariff schemes and hundreds of billions of unlocked project finance was that governments effectively eliminated the market risk by guaranteeing a fixed tariff under a take-or-pay structure, typically for at least 20 years. The market risk was substituted by the counterparty risk of typically highly creditworthy sovereigns.

Similar situations are still hard to find in the energy storage sector, even when including projects with corporate counterparties. With the exception of a few geographies, merchant projects are still dominant, with the specific market risk depending on the application. This renders nonrecourse project financing often impossible, or adds substantial risk premiums and puts stringent limits on leverage or coverage ratios, resulting in fairly high cost of capital. In many cases, some form of corporate balance sheet backing will be required for structured financing solutions.

Given the difficulties around bankability, unconventional, non-bank sources of capital such as specialist funds are currently still dominating the sector and need to be accessed.

That said, project financing should not be confused with schemes that amount to lease financing, particularly popular with C&I, but also increasingly with residential customers. In this case, the majority of the risks are assumed by the corporate or private end customer, and traditional tools from corporate and consumer finance can be employed, including the securitization of lease portfolios.

In summary, financing for energy storage projects is available but requires careful structuring depending on the use case, underlying commercial arrangements and risk allocation. In fact, more than USD 820M was invested in battery projects in 2016, a massive increase from the year before. The bulk of this funding went to no-money-down, distributed energy storage offerings or projects based on a take-or-pay contract.

In summary, these are the key ingredients successful energy storage business models should reflect. As outlined above, they can be implemented in multiple ways. The optimal “recipe”, however, depends on the individual company’s situation and needs careful evaluation as it will impact various business-specific, interrelated elements such as customer channels, partnerships and resources.

For questions or comments, please contact Apricum Partner Florian Mayr.

This article was originally published on Energy-Storage.News