The rise and fall of feed-in tariffs

By the end of 2018, only seven years after the introduction of a national feed-in tariff (FIT) support scheme in 2012, China was home to one third of the world’s cumulative photovoltaic capacity, with ~173 GW of cumulative PV installations. The scheme was designed to facilitate the local deployment of solar PV installations.

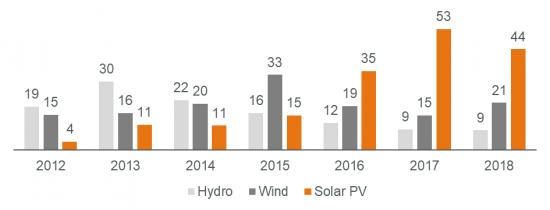

Figure 1: Annual renewable energy capacity installations in GW, 2012–2018

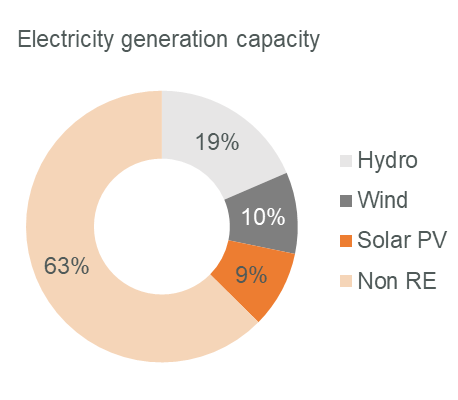

The 173 GW cumulative installed capacity made up 9% of the total existing power generation capacity in 2018. Low capacity factors in solar PV led to a 2.7% contribution to electricity generation. Meanwhile, coal’s share dropped below 60% in 2018.

Figure 2: Sources of electricity generation capacity and total generated electricity in 2018

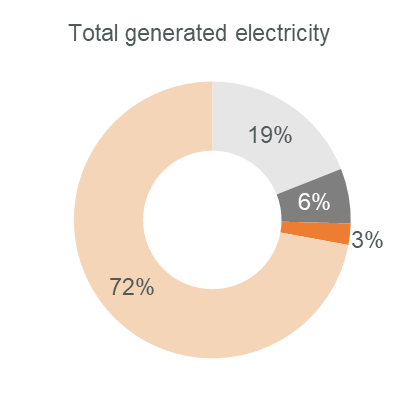

Last year, China managed to install a total of 44.26 GW (vs. 53.06 GW in 2017), with 24.4 GW and 19.96 GW of installations in H1 and H2 respectively. This year, installations from January until September 2019 witnessed a drop by 45%, with only 15.99 GW, according to China’s National Energy Administration (NEA). This slash in installation volumes was due to the NEA’s decision on May 31, 2018 to cease the approval of any new subsidized projects until further notice. The decision was taken against a backdrop of RMB 200B in outstanding FIT payments for renewable energies (i.e., wind, solar, biomass) and off-grid systems, with PV claiming a 40% share of the debt.

Figure 3: China PV H1 installations, 2014–2019

Attaining long-awaited visibility

In early January 2019, after eight months of no visibility on the market, the NEA released a statement outlining the development of so-called wind and solar PV grid-parity projects (i.e., projects that are financially viable without subsidies). This grid-parity policy covers 15 provinces, and the 2019–2020 period is considered a trial run. Local governments are encouraged to provide on-site support such as identifying state-owned land (allowing the exemption of land-use fees), guaranteeing off-takes, or, if this is not feasible, allowing local electricity trading. However, the most central item of the statement is the minimum PPA duration of 20 years for local grid companies.

On April 10, 2019, the NEA released a more comprehensive consultation paper titled “Work Plan for the Construction of Unsubsidized (Grid-Parity) Projects for Wind and Solar PV.” It contains the following key points:

- Incentives for solar PV projects approved by 2018 to be voluntarily converted into unsubsidized/grid-parity projects. If in agreement, grid companies should earmark such power consumption as their highest priority. Unsubsidized projects commissioned in 2019 are given second priority.

- Abolishment of previously awarded approvals from the past two years for solar PV projects which have not started construction (or applied for an extension), regardless of the companies’ promise to continue the construction.

- Participation as a new project in the national unified bidding process in 2019 for projects wishing to continue construction. At present, approved unconstructed PV projects – with and without quota – amount to >7.8 GW and >32 GW, respectively.

- Suspension of projects requiring state subsidies, i.e., provinces and regions should not have conducted bidding rounds for solar PV projects requiring state subsidies until the first batch of grid-parity projects in 2019 has been allocated by the national authorities.

- Submission of the first batch of projects to the national authorities by April 25, 2019 for regions and provinces that can facilitate grid-parity PV projects (with projects approved in 2018 and willing to convert into a grid-parity project to be included). Other provinces had until May 31, 2019 to submit the respective national subsidy project competition plan to the NEA.

- The effectiveness of the consultation paper ends on December 31, 2020.

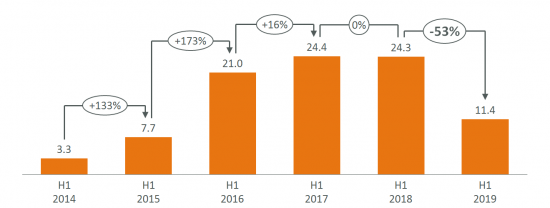

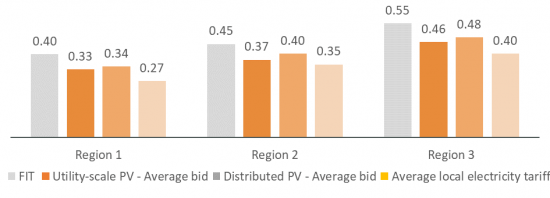

Twenty days later, on April 30, 2019, the price bureau of China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) released a notice called “Improving Issues Related to Feed-in Tariffs (FIT) for Solar Photovoltaics.” The document stipulates the following FITs (including tax) for centralized PV, i.e., ground-mounted systems across three designated regions in China: Region 1, with 0.40 RMB/kWh; Region 2, with 0.45 RMB/kWh; and Region 3, with 0.55 RMB/kWh.

FITs for so-called “village-level” poverty alleviation PV projects remain unchanged, at 0.65 RMB/kWh, 0.75 RMB/kWh and 0.85 RMB/kWh for regions 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Commercial and industrial (C&I) distributed solar PV projects designed for “self-consumption with feed-in of the excess power to the grid” are subject to a FIT of 0.10 RMB/kWh. However, projects seeking a 100% grid feed-in are subject to the same FITs applied to centralized, ground-mounted systems. Residential solar PV systems are entitled to a FIT of 0.18 RMB/kWh and are included in the 2019 FIT subsidy budget. In 2019, up to approximately 5 GW of residential systems are estimated to be installed.

The document points out that the aforementioned FITs – regardless of type and operation mode (FITs for C&I with self-consumption remain unclear) – are intended as guidance and therefore subject to competition. This means that local authorities should conduct auctions in coordination with the central government and that the results will enter a unified national bidding process from which the NEA selects the most competitive projects. The notice became effective on July 1, 2019.

Since May 31, 2018, it took the relevant authorities 13 months to finally release their 2019 Solar PV FIT Policy and restore the required visibility on the market. However, this raised a number of unclarified questions, e.g., how will the central government deal with PV systems that were connected to the grid between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, totalling an estimated 28–30 GW? Will they be included in the renewable energy subsidy budget for 2019 (RMB 2.25B), with corresponding last year’s FITs? If so, how much of the earmarked budget might then be left to support new projects until the end of 2019?

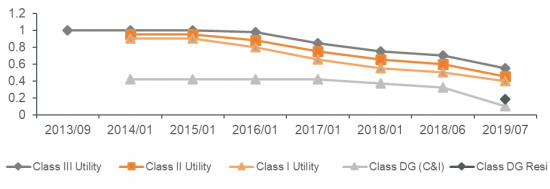

Figure 4: Solar PV FIT development, 2013–2019 in RMB/kWh

The first unsubsidized batch

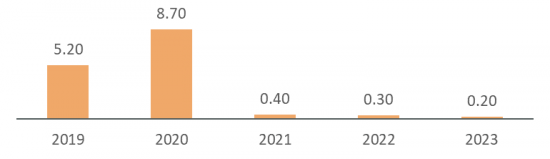

On May 20, 2019, China’s NDRC and NEA jointly released the first batch of approved grid-parity projects for 2019, for both wind and solar PV, with a total of 20.76 GW. These are split into wind (4.51 GW), solar PV (14.78 GW) and so-called “distributed trading pilot projects” (1.47 GW). The announced solar PV grid-parity projects are distributed across 16 provinces. Guangdong Province, with 2.38 GW, took the lead. The commissioning dates of these 168 projects range from 2019 until 2023. Larger projects, such as a 300 MW project in Guangxi Autonomous Region, are planned to be constructed in up to three phases. It is expected that additional batches of grid-parity projects will follow in the coming years.

Figure 5: First batch of 2019 solar PV grid-parity projects in GW

As for grid-parity projects, in August and September 2019 the three provincial governments of Jilin, Inner Mongolia and Jiangsu released the bid results of 1.5 GW of “Top Runner” projects. Overall, not only did bid prices drop by 8-25% in the course of the 16 months since the last Top Runner bidding, but the bid price for the project in Dalad, Inner Mongolia, was also approximately 2% below the local coal benchmark price of RMB 0.2829/kWh (~4 EURct./kWh).

The auction

On July 10, 2019, China’s NEA released the result of the nation’s first national unified auction. The auction was dedicated to solar PV projects seeking subsidies with plans to be grid connected by the end of the year. The number of submitted solar PV projects amounted to 4,338 with a combined capacity of 24.55 GW. However, only 3,921 projects with a capacity of 22.78 GW received official approval. A breakdown of the 22.78 GW shows: 366 utility-scale projects with a capacity of 18.12 GW (79.5%), 473 distributed PV projects with 0.56 GW (2.5%) and 3,082 self-consumption projects with a capacity of 4.10 GW (18%).

Overall, 23 provinces participated in the bidding process. The most favored was Guizhou Province with >3.6 GW, followed by Shaanxi Province with 3 GW and 13 other provinces, each with >1 GW to be installed. Gansu Province and Xinjiang Autonomous Region were not allowed to participate due to prevailing grid curtailment rules. Eight provinces, including Heilongjiang, Jilin, Yunnan and Hainan, did not participate in the auction due to limited grid capacities.

Approved feed-in tariffs range from 0.2795 RMB/kWh (for a 100 MW plant in Ningxia Autonomous Region) to 0.5500 RMB/kWh (for a 24 kW plant in Chongqing Municipality). The average submitted tariff was 0.3281 RMB/kWh.

Tariffs for projects which fail to reach the commissioning deadline of December 31, 2019 are subject to a quarterly tariff reduction of 0.01 RMB/kWh until Q2, 2020. Otherwise the FITs will be revoked and the project canceled altogether.

The large share of projects in the utility scale proves that today only larger projects allow for low generation costs and consequently for competitive bids. The lowest bid was at 0.2795 RMB/kWh (~4 EURct./kWh). To potentially increase the share of distributed PV in upcoming auctions, other criteria than the submitted FITs might be taken into account when awarding projects.

Figure 6: 2019 first auction results and tariffs in RMB/kWh by region

Upon concluding the nation’s first bidding round, 18 larger companies (e.g., State Power Investment Corporation, Sungrow, Guangdong Nuclear Power, Tongwei, Longi, Jinko Solar, TBEA, GCL, Trina Solar and Three Gorges) were awarded 8.8 GW of grid-parity projects and 8.6 GW of FIT-supported projects. The combined 17.1 GW capacity represents 46% of the total projects awarded in 2019. The result indicates that the Chinese solar PV industry will strive towards a greater consolidation in the months and years ahead.

Unstoppable upstream growth

Despite the 53% cut in domestic demand for PV in H1 2019, the upstream PV industry in China is witnessing growth. Production outputs have increased in the same period by 8.4%, 26%, 30.8% and 11.9% for polysilicon, wafers, cells and modules, respectively. Consequently, exports for cells and modules have increased by 50% and 45.2%. However, a higher local demand for cell manufacturing has decreased wafer export by 34%.

A staggering USD 10.6B increase in exports income during H1 is the result of an overall 31.7% increase in PV exports (i.e., PV wafers, cells and modules). Major export destinations for modules in particular included India, Japan, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, the Netherlands, Spain and Vietnam. Interestingly, the share of exported higher-performing modules, i.e., 350–400 W, increased to 25.5% compared to just 8.8% for the entire last year.

Transitional prospects and beyond

In summary, the consultation paper shed light on how China’s National Energy Administration intends to move forward in the remaining period of the 13th “Five Year Plan” – a period considered “transitional” for the PV industry, meaning the Chinese market will evolve from a subsidy-driven market to a home for both grid-parity and FIT-supported projects. It is expected that the market will eventually enter a subsidy-free era starting from 2021 or slightly later. It is worth noting that this transition, i.e., elimination of FITs for both solar PV and wind by 2020, was already indicated in the “Three-Year Clean Energy Consumption Action Plan, 2018–2020,” released on November 30, 2018.

In the context of how to deal with past and future FIT payments, China’s Ministry of Finance released a notice indicating a fundamental change in September 2019. It foresees a potential cancelation of the 8th Renewable Energy Catalogue and proposes an online application through NEA’s Information Management Platform and a final disbursement via local grid companies within 10 working days in the future. The immediate impact of these proposed changes is difficult to assess, given that at the time of writing no final decision was officially released.

Equally impactful could be the introduction of a base price and floating mechanism for the coal benchmark price announced by China’s National Development and Reform Commission in late September. Accordingly, from January 1, 2020 the coal benchmark might fluctuate by -15% and +10% annually. The latter increase would only apply from 2021 onward in order to avoid a price increase, especially for the C&I sector during the first year of its introduction. However, a drop of the local coal benchmark price by 15% could consequently challenge the competitiveness of grid-parity projects and eventually lead to postponements or even cancelation of such projects planned for next year.

The developments throughout the first three quarters of 2019 have been dampening PV installation volumes in China. Earlier hopes that the third and fourth quarters would see a revived demand did not materialize; instead, demand appears to continue to be moderate. While our view of Chinese PV demand for the entire year was still 36–44 GW in the summer, in light of this rather sobering market reality we have now substantially decreased our forecast to 20–24 GW. Although the Chinese market outlook will continue to be uncertain for some time, we expect demand to pick up again in the coming years. Also, the good news is that the continuing attractive prices for PV have unleashed a wave of demand outside of China, which means that the global PV market will react in a less sensitive manner to the volatility of the Chinese domestic market going forward.